(Most fashion photos are from Vogue.com)

I've been eager to talk about Rick Owens for a while now -- not just Rick Owens the designer I adore, not the sharp-profiled patron saint of Goths everywhere, but rather Rick Owens as a cultural force, and an oblique successor to the avant garde of the eighties and the cosmopolitan minimalism of the nineties.

But let's start with his Spring/Summer 2014 collection. It gained a lot of (well deserved) attention by casting American step teams instead of models.

You can watch the full video of this really inspired performance here:

Thing you will notice first is the diversity of the models, which makes sense: they were not selected by a casting director, but came as an entire group of living, breathing American students, with bodies of different heights, builds, weights and of course colors.

Another thing that immediately jumps to mind is how easy these clothes are to move in. And how GOOD they look on these women -- all of them. This is really the quintessential Owens' clothing -- interesting but not imposing or assuming, clothes that are mostly black or white or dust colored, cut in an inspiring and often mind-boggling way, and yet so easy. A disclaimer is perhaps in order: I love Rick Owens' clothes. I wear them a lot; they are blank and anonymous. And yet people who also love him will recognize his clothing immediately -- by the drape, but the flattering skim of unraveling and asymmetrical jersey, by a sharp cant of the shoulder.

The thing about this show is how much it says about fashion as an institution -- how often the barriers we see are artificial; and it also seems to be poking a bit of fun. It's as if it says, you want more diverse runways? You don't need more casting directors or a heavily regulated model industry; you can just grab a group of people from anywhere in the real world, and here you have it. (Of course now casting "real people" in the runway shows is a trend. I will not say that Owens pioneered it -- but he certainly got a lot of attention when he did.)

I would not call Owens clothes derivative by any means, as his aesthetic is all his own; and yet it would be a mistake to argue that he has no antecedents. The palette and the indifference in separating eveningwear from streetwear roots him firmly in the nineties, to the works of the Amsterdam six (especially Ann Demeulemeester), as well Yohji Yamamoto. Yamamoto has become a rarefied legend, and yet he was one of the first avant garde designers to actually look to the street, to the "sneaker culture" as he calls it, and to incorporate some very mundane references into the exquisitely cut clothes.

Of course there are also more direct points of comparison between Yamamoto and Owens: both reject the explicitly feminine silhouettes, tending instead toward the androgyny. It is never tight but skimming, it is boxy but flattering, bizarre and yet utterly enchanting.

It is a quintessential Owens, and we can see a similarity to a Spring 2014 piece:

Evolution for sure, but hardly a dramatic leap. As the show progresses, however, Owens abandons his usual skimming/concealing of the body and goes toward the downright distortion:

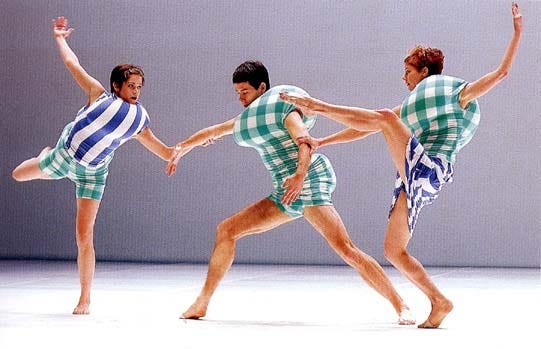

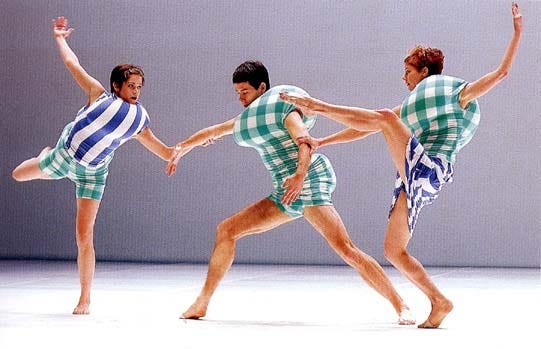

At this point, one has to recognize that this distortive approach, this refusal to enter the flattering/unflattering dichotomy harks back to Rei Kawakubo, another Japanese avant garde designer (who was honored in this year's Met Museum Costume Institute Exhibit), who refused to even consider the question and went straight for the body distortions, like in her famous 1997 collection:

And all doubts disappear when Owens walks out this look:

The manipulation of jersey, the color is all Owens but the shape is unmistakably referential of Kawakubo. And listen, I am the first to argue that runway presentations are about art first and commerce second, that complaining about runway looks not being wearable is missing the point -- a bit like judging a painting by how well it matches your living room color scheme. And yet...

These are professional ballet dancers performing in those lump dresses from Kawakubo's collection. And the attention to the movement, to the three-dimensional reality of clothing and athletes' bodies -- who, unlike models, inhabit the clothes fully instead of walking them down the runway -- brings this all together for me. That Spring 2014 show that was also shown on bodies of dancers.

So to me Rick Owens' 2018 show is a love letter -- to other designers, to the evolution of his vision, and to the bodies that move and inhabit clothes, bodies that revealed and concealed, distorted and embraced. It is a love letter to movement in all senses of it -- dance, time, music, human body -- and I am grateful for it. This letter came at the right time.

I've been eager to talk about Rick Owens for a while now -- not just Rick Owens the designer I adore, not the sharp-profiled patron saint of Goths everywhere, but rather Rick Owens as a cultural force, and an oblique successor to the avant garde of the eighties and the cosmopolitan minimalism of the nineties.

But let's start with his Spring/Summer 2014 collection. It gained a lot of (well deserved) attention by casting American step teams instead of models.

You can watch the full video of this really inspired performance here:

Thing you will notice first is the diversity of the models, which makes sense: they were not selected by a casting director, but came as an entire group of living, breathing American students, with bodies of different heights, builds, weights and of course colors.

Another thing that immediately jumps to mind is how easy these clothes are to move in. And how GOOD they look on these women -- all of them. This is really the quintessential Owens' clothing -- interesting but not imposing or assuming, clothes that are mostly black or white or dust colored, cut in an inspiring and often mind-boggling way, and yet so easy. A disclaimer is perhaps in order: I love Rick Owens' clothes. I wear them a lot; they are blank and anonymous. And yet people who also love him will recognize his clothing immediately -- by the drape, but the flattering skim of unraveling and asymmetrical jersey, by a sharp cant of the shoulder.

The thing about this show is how much it says about fashion as an institution -- how often the barriers we see are artificial; and it also seems to be poking a bit of fun. It's as if it says, you want more diverse runways? You don't need more casting directors or a heavily regulated model industry; you can just grab a group of people from anywhere in the real world, and here you have it. (Of course now casting "real people" in the runway shows is a trend. I will not say that Owens pioneered it -- but he certainly got a lot of attention when he did.)

I would not call Owens clothes derivative by any means, as his aesthetic is all his own; and yet it would be a mistake to argue that he has no antecedents. The palette and the indifference in separating eveningwear from streetwear roots him firmly in the nineties, to the works of the Amsterdam six (especially Ann Demeulemeester), as well Yohji Yamamoto. Yamamoto has become a rarefied legend, and yet he was one of the first avant garde designers to actually look to the street, to the "sneaker culture" as he calls it, and to incorporate some very mundane references into the exquisitely cut clothes.

Of course there are also more direct points of comparison between Yamamoto and Owens: both reject the explicitly feminine silhouettes, tending instead toward the androgyny. It is never tight but skimming, it is boxy but flattering, bizarre and yet utterly enchanting.

From Yohji Yamamoto himself: "Men's clothing is more pure in design. It's more simple and has no decoration. Women want that. When I started designing, I wanted to make men's clothes for women. But there were no buyers for it. Now there are. I always wonder who decided that there should be a difference in the clothes of men and women. Perhaps men decided this."

(Not surprisingly, I adore Yamamoto, even more than Owens.)

But if it was all there were all to Owens -- the reliance on black and the asymmetry, the unraveling seams and the imaginative cuts -- there would be no explanation for his most recent show, Spring 2018.

It starts out mildly enough:

It is a quintessential Owens, and we can see a similarity to a Spring 2014 piece:

Evolution for sure, but hardly a dramatic leap. As the show progresses, however, Owens abandons his usual skimming/concealing of the body and goes toward the downright distortion:

At this point, one has to recognize that this distortive approach, this refusal to enter the flattering/unflattering dichotomy harks back to Rei Kawakubo, another Japanese avant garde designer (who was honored in this year's Met Museum Costume Institute Exhibit), who refused to even consider the question and went straight for the body distortions, like in her famous 1997 collection:

And all doubts disappear when Owens walks out this look:

The manipulation of jersey, the color is all Owens but the shape is unmistakably referential of Kawakubo. And listen, I am the first to argue that runway presentations are about art first and commerce second, that complaining about runway looks not being wearable is missing the point -- a bit like judging a painting by how well it matches your living room color scheme. And yet...

These are professional ballet dancers performing in those lump dresses from Kawakubo's collection. And the attention to the movement, to the three-dimensional reality of clothing and athletes' bodies -- who, unlike models, inhabit the clothes fully instead of walking them down the runway -- brings this all together for me. That Spring 2014 show that was also shown on bodies of dancers.

So to me Rick Owens' 2018 show is a love letter -- to other designers, to the evolution of his vision, and to the bodies that move and inhabit clothes, bodies that revealed and concealed, distorted and embraced. It is a love letter to movement in all senses of it -- dance, time, music, human body -- and I am grateful for it. This letter came at the right time.